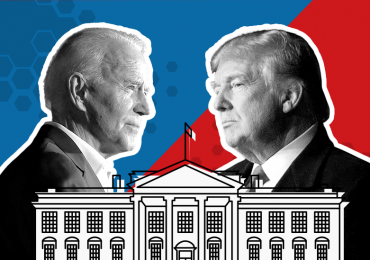

When Joe Biden clinched the presidency Saturday, climate activists breathed a sigh of relief.

After four years of President Donald Trump’s denying the science of climate change and dismantling or rolling back more than 100 environmental protections, climate experts knew the stakes in the election could not have been higher.

“The climate movement was very clear-eyed about just how crucial this election was, so I think that made anxiety run pretty darn high,” said Katharine Wilkinson, editor-in-chief of Project Drawdown, a coalition of researchers and scientists who are working on climate change solutions. “Science tells us we don’t have time for another four years of a Trump administration. We don’t have time for four more years of bailing out failing fossil fuel companies and four more years of moving backwards.”

Wilkinson, a co-founder of the All We Can Save project, a women-led climate nonprofit, said the past few days have been “definitely a roller coaster.” Now, experts say they are eager for the new president to get to work on tackling the climate crisis.

But if Republicans keep control of the Senate, there may be challenges as Biden tries to turn his plans into action. Most climate activists have applauded Biden’s climate plan, which includes investing $2 trillion over four years and aims to achieve a 100 percent clean electricity standard by 2035.

Democrats gained a Senate seat but need to pick up two more to reach 50 and assume control, with Vice President-elect Kamala Harris as the tiebreaking vote. Two Senate seats in Georgia, now held by Republicans, appear to be advancing to runoff elections on Jan. 5, which means the makeup of the Senate could hang in the balance until then.

Still, Biden can make progress on climate issues even if the Senate majority remains in Republican hands, said Shiv Someshwar, a visiting professor at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs.

It is unlikely that sweeping legislation along the lines of the Green New Deal could move forward without a Democratic-controlled Senate, but a Biden administration can still address some short- and long-term impacts of climate change, he said.

“While massive investments may not be possible, the Biden administration could be active in rolling out regulations that are designed to limit [greenhouse gas] emission and those that minimize climate risk in future on public and private assets,” said Someshwar, who is European chair for sustainable development and climate transition at the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po) in France.

That could include supporting the national adoption of fuel efficiency standards for cars and trucks like those that have been introduced by California Gov. Gavin Newsom, Someshwar added.

Gina McCarthy, president and CEO of the Natural Resources Defense Council, said that if the public demands action on climate, sluggish lawmakers may be forced to take note.

“Even if the U.S. Senate doesn’t lead on strong climate policy, they can be dragged along, and we can expect to see progress regardless of who is controlling the Senate,” she said Thursday, two days after the election, at a news conference with several prominent environmental organizations.

McCarthy, who was administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency during the Obama administration, said fighting climate change “isn’t just about protecting polar bears in faraway places — it’s essentially about protecting people, our families, right here and right now.”

Climate experts are also eager for Biden to repair the United States’ reputation internationally. The day after the election, the U.S. formally exited the Paris Agreement, a global pact among more than 185 countries to curb emissions and keep the rise in average temperatures below 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, or 2 degrees Celsius. Trump announced his intention to withdraw from the landmark climate accord in 2017, and the process was initiated a year ago.

Biden has said he intends to rejoin the Paris Agreement, but the U.S. has a lot of ground to make up to meet the goals of the accord. And it is becoming increasingly clear that deeper cuts to emissions will be necessary to limit global warming to below 3.6 degrees F, said Michael Mann, a climatologist and professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University.

“The sobering reality is that even if every country meets their commitment under Paris (and many, including the U.S. and E.U. are currently falling short), that gets us less than halfway to where we need to be,” he said in an email. “Paris is a good starting point, but we need to go well beyond Paris now to achieve the reductions that are necessary.”

Mann acknowledged, however, that Biden’s victory favors “an atmosphere of global cooperation.”

And Wilkinson said that while plenty of challenges lie ahead, it was heartening to see climate politics play such an important role this election cycle.

NBC News exit polls of early and Election Day voters indicated that two-thirds of voters said they believe climate change is a serious problem. The same polls showed that Biden won about 7 in 10 voters who see climate change as a serious problem.

“There are lots of climate silver linings in this election,” she said. “Of course, the big question mark is what the makeup of the Senate looks like, and will we have the full suite of levers for bold climate action in 2021, but I’m cautiously hopeful.”

Leave a comment